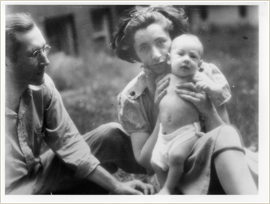

Something a little different this time, a short story I wrote a while ago based on anecdotes my father told me.

DUST

Dust can sit pretty deep on a back road in California at the end

of summer, months with no rain to damp it down, just the occasional car

to stir it up. It was a road like that, and the woman had been standing

beside it a long time looking at the tracks in the dove-colored dust.

The slanting light of late afternoon made the tire tracks seem deeper.

The dog tracks looked huge, and she imagined the little explosions of

dust some ordinary dog must have made to excavate these mastiff-tracks.

Then she imagined—no, remembered—the feel of that same dust on bare

feet. Infinitely soft, soothing, lulling, so that the inevitable hidden

rock or thorn or upturned bottle cap came as a surprise and a betrayal.

She was so lost in soft dry thoughts that when she noticed the noise,

she knew she had been hearing it a long time without noticing. She

looked up and saw a Model A so evenly coated with a bloom of dust she

knew the car had been shiny black before it turned onto this road.

Someone loves that old girl, she thought. Through the dusty windshield

she could see that the driver wore a felt hat, but as he slowed down and

came past her, his face suddenly clear in profile through the open side

window, he looked younger than a hat-wearer should. Dressing the part,

she thought, and smiled. He must have caught that out of the corner of

his eye. He gave a little wave of acknowledgment.

She closed her eyes as the dust billowed up around her, and an

image ran through her mind, an instant replay of the car’s approach. She

saw a yellow and black license plate, small numbers...small numbers

from a long time back, not a classic car plate, and at the same time it

occurred to her that the face had looked familiar. She opened her eyes

wide, but she couldn’t see the back plate for dust. She was sure,

though. She started to follow the tracks. She had nothing particular to

do and no one expecting her, but if she had, she would have followed

that car anyway.

This latest set of tracks was easy to pick out, and as she

walked, she had time to reconsider. The most obvious explanation was not

that she had walked into a different decade but that she had some

relative around here she wasn’t aware of. No, the most obvious

explanation was that it had been a trick of the light, and the man

looked no more like those pictures of her father as young man than any

one of a thousand handsome young men might. But it wasn’t just the face.

Something—the way he waved, or sat, or wore his hat—something

reminded her of her father as she had known him. He had been

forty-two when she was born so he would be what, in her earliest

memories? When does a parent become something separate in a child’s

eyes? The man in the car was younger than forty, maybe even younger than

thirty. The potty wouldn’t be tied to the back bumper for the baby she

once was, and thank goodness for that. Her father had told her about the

trip from Detroit to California, him rinsing out the potty at gas

stations. He had said to her once that when he was growing up, he had

never imagined living past forty. Nothing morbid, just that forty seemed

too far away from his young self to think about at all. She had passed

forty, and forty-two, a while ago.

She didn’t know how far it was to the town ahead. She had come to

her friend’s country place on a paved road and had only meant to walk a

little ways down this side road before she unpacked and fixed something

for dinner so she hadn’t looked for a map, but her friend had said

there was a town this way, just a crossroads really, a backwater. A

dusty backwater, it would be, unless they’d paved the road through town.

The country greens were dulled with dust along the road, and her shoes

were coated. No other cars came to obscure the tracks she followed. She

thought about the dust bowl—just words to her, and black-and-white

photographs in books, but her father had probably seen farms buried in

dust, or for sure had talked to refugees fresh from those farms. Now (if

she was in Now, and not in Then) now it was drought time here in

California where a lot of those refugees had fled to. And maybe another

depression on the way. Her father had predicted one for years but hadn’t

lived to see it.

A lot of things he hadn’t lived to see. He’d taken the

revelations about Stalin in stride, but what would he think about the

downfall of the Soviet Union? All those dreams come to dust. What if

that was her father up ahead, drinking five-cent coffee in some

time-warp café? What on earth would she say to him? She didn’t think

he’d ever put all his hopes in the Soviet Union the way some had. She’d

heard him say the party was too turned toward Europe, didn’t pay enough

attention to American traditions. But till he gave up on it, the party

had been the best vehicle he’d found for his hopeful energy, and what

could she tell him that would be better?

She thought about his fascination with inventions, that engineer

he had invested in, slim and hat-wearing like himself, to develop a

machine for refining gold ore without using water so it could work in

the desert. She remembered that story he had come back from one of his

trips to the desert with, about stopping in one of those little

combination store, coffee shop and gas stations on the road, having a

cup of coffee, and a guy bursting into the store, seemingly out of

breath, saying “Did you see that?” “What?” somebody asked. “That dog!

That black dog! He took a big drink out of that pail out there and it

wasn’t water, it was gasoline! That dog took off running faster’n any

dog I’ve ever seen. I followed ‘im, fast as I could go, see what happen.

Mile, mile and a half, I tell you. Found the dog lying at the side of

the road.” “Was he dead?” her father asked. “No,” replied the man, “he

run out a gas.” And the man dodged out of the store again before anyone

could react. She remembered her father’s delight both at the joke itself

and at being so well and truly caught.

Her mother had wanted him to invest in real estate, which as a

carpenter he knew about, but he had that Yankee propensity for monkeying

around with things, seeing how they could go better. He was as drawn to

tinkering with social systems as his engineer friend was to figuring

out how to make that machine work. She sure wasn’t about to warn him not

to invest in it. He’d never gotten any cash return on it, but he’d

probably gotten his money’s worth in enjoyment.

Well, if this was a time warp, an afternoon in 1930, maybe she

didn’t want to talk to him anyway. Maybe all she wanted to do was to see

him walk around, to see his shy enthusiasm in the young body she had

never seen. He had grown old and in most ways wise without losing that

gusto, but in her lifetime it had come out in arguments and articles and

meetings and election campaigns. All that was left of his days on the

barricades were those stories he told so well. The hunger marches, the

free speech fights, filling up jails.

Maybe that was why she wanted to see him, so she could see those

stories and tell them as well as he had or at least well enough to use

them at all. His voice would be the same, she knew that, because she

remembered the time when he came home from a trip to Detroit talking

about finding a name in a phone book and calling up an old school chum

he hadn’t seen since the eighth grade. He said the man’s voice was so

like the boy’s that the years had melted away as they never would have

if they’d been face to wrinkled face. They hadn’t wanted to follow up

the telephone conversation with a visit in person. And her father’s

voice, on tape, was all she had left, really, and she didn’t even know

where those tapes were.

That wasn’t all she had, of course. She knew that whatever she

found in town, when she got back to the cabin (if she got back to the

cabin) she would take the top off the toilet tank and see if she could

do something about that leak. She shivered and wished she had brought a

sweater and knew a sweater wouldn’t help.

And here was the first building coming into view, a

board-and-batten house with blue trim. No TV antenna or satellite dish,

no car parked outside, so she had no clue either way. The pavement

started this side of the house. Beyond the house she saw an old gas

pump, probably standing in front of a tiny store, and she wouldn’t know

till she got there whether the pump was working or not and whether she

would see this year’s prices if it was. She slowed down, not wanting her

possibilities narrowed either into ordinary disappointment or into

something too strange to cope with.

The Model A was nowhere in sight. There was, of course, a third

possibility. This could be 1930, and her father could have driven

through town and not stopped, and she would be both disappointed and

scared out of her wits. She came up to the old-fashioned pump. The gas

prices were this year’s. She went into the store. There was a counter

with a woman about her age behind it and two men in John Deere caps

sitting on stools with thick tan mugs in their hands, and all three

people were shaking their heads and smiling. She sat down, ordered a cup

of coffee, and looked from face to face. One of the men chuckled.

“You’re gonna think I’m telling you a story,” he said, “but a young man

just run in here all out of breath and says ‘Did you see that?’ ‘What,’ I

says, and he says, ‘That dog! That black dog!’”

©2010 by Nancy Schimmel

Jan McMillan

This

was a lovely story. Having lost my dad when I was a year old I have

created him in my mind but never written about him really. You've

inspired me to try to do that. I think I would have liked your fater!

Jan

Sunday, February 21, 2010 - 07:10 AM

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

DUST