I

have been riding madly off in all directions, first to a women’s

storytelling retreat in Southern California’s high desert, where I

worked on making the story of the Ku Klux Klan raid on my grandparents’

house into a performance piece, then the next weekend to a writers’ and

artists’ retreat in the redwoods near the Russian River where I worked

on the chapter of the bio that grew out of my blog piece “I Was Born in

Omaha” and wrote a tune for some lyrics that had been sitting around for

a couple of years, then two days to breathe and do laundry and off to

the MusicEdVentures conference in Minneapolis, arriving just ahead of eighteen inches of snow.

The

folks in Music EdVentures are mostly music teachers or classroom

teachers using singing games to teach music, English as a second

language, math, getting along with other kids, listening skills, all

sorts of things. I think the ESL part is easiest to describe. Children

are singing “You put your right foot in” while they are putting their

right foot in, so the words are reinforced visually (by seeing the other

kids doing the action) muscularly, musically and orally. And repetition

is built into the games so it’s not boring. There were about five

English teachers there from Japan who use this method, and Judy Fjell,

who got me going to these conferences, was leaving the following month

for Japan to do workshops there.

I

also heard exciting news on the use of games in socialization. Children

who have a hard time relating to others—even some autistic children—can

do so within the safe structure of a singing game which not only tells

them to take a partner’s hand but cues them by the musical phrasing as

to when they should do it and with whom. Naturally, we did a lot of

singing games, which helped keep us alert in spite of fluorescent

lights, canned air, and other hotel amenities.

The following weekend I went to part of a symposium at Mills College, right next door in Oakland, put on by the Art IS Education office

of the Alameda County School District. More neat stuff, including a

local parents’ group, Arts Active Parents, which is petitioning for arts

for every child in every school, every day. The national group doing

this is Keep Arts in Schools.

All

this is, of course, in reaction to President Bush’s “No Child Left

Behind” nonsense which is leaving the arts, sciences and humanities

behind for a lot of children, as it only counts test scores for math and

reading skills. Best story from that day: Berkeley High has a small

school called AHA (Arts and Humanities Academy) which did a month-long

project on the First Amendment and the arts. They had guest artists talk

about running into censorship problems, and a civil liberties lawyer.

The students thought up, on their own, this piece of street theater:

they spread out over the whole BHS campus reciting the First Amendment

into their cell phones.

Then

I picked up the current issue of Mothering magazine for the cover

article, “Bring Back Recess: Why Kids Need Play.” A lot of schools are

eliminating recess to have more time to drill kids so they will pass

those standardized tests. Teachers’ jobs and even the continued

existence of the school depend on their passing. Actually, children pay

attention better if they do have recess to blow off steam, and folks

have even done studies showing this to be true. And in Japan, whose

education system is held up as an example, children have recess more

often than in most schools here. Alas, only three states -- Missouri,

Louisiana and Illinois -- require elementary schools to offer recess,

and it is in poverty areas where children have less access to parks and

backyards that the schools have the least recess time. So now we have to

have a group promoting and protecting recess, and it’s IPA/USA, The American Association for the Child’s Right to Play.

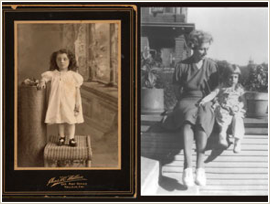

My

parents and I grew up in a time when children’s play was unstructured

or was structured by the children themselves in games like tag or jump

rope or singing games which were not taught by adults but learned from

slightly older children. As kids, my mother and I had music lessons and I

had ballet, my father had chores, but we had time for street games and

fantasy play as well, and no television.

DON’T BOTHER ME

Words and music by Malvina Reynolds; copyright 1957 by author.

Don't bother me, I have some things to do,

Don't bother me, I have to tie my shoe,

Don't bother me, I'm standing like a tree,

Spin like a top, I can't stop,

Don't bother me.

Don't bother me, I have to hurry by,

Don't bother me, I'm learning how to fly,

Don't bother me, I'm buzzing like a bee,

Roll down the hill, can't keep still,

Don't bother me.

Don't bother me, I'm thinking something nice,

Don't bother me, I'm sliding on the ice,

Don't bother me, I'm singing "Toodle-dee,"

Boat on the bay, sailing away,

Don't bother me.

Music to this song is in Tweedles and Foodles for Young Noodles. (when you get to the site, scroll way down)

Here’s a piece I wrote a good while ago on how we played when I was young:

This

memory is from the fourth grade, living on Cherry Street in Berkeley,

in the same neighborhood--but not the same apartment--where we had lived

since we came to Berkeley when I was a toddler.

Joseph

Baron was a year older than I. He arrived in our neighborhood with a

great advantage—he moved into the designated haunted house, a two-story

white wood classic around the corner and across Stuart Street from the

four-room apartment we lived in. The house was not rundown, but it was

of an earlier era and had stood vacant for a while, and that was enough

for us. Luckily, Joseph was a boy who could rise to the occasion. His

imagination riddled the house with secret passages and transformed the

neglected back yard into a place of mystery and fantasy.

He

claimed that a man had hanged himself from the huge tree at the back of

the deep yard, and indeed when we dug holes under the tree we did find

some bones—who knows what kind. This was a passing interest, however.

Joseph’s abiding passion was playing Bambi. We acted out every adventure

in the book and others of his invention. (I had not read Bambi—he was

in charge of this.)

We

also planted a tiny garden by the house. I remember crumbling and

sifting the dirt to a smooth powder. The seeds we planted were going to

produce perfectly symmetrical carrots in such soil. If they grew. I

don’t remember that part.

The

interior of the house was not neglected at all. The highly polished

floors were the downfall of Joseph’s mother’s little black-and-white

dog. He would come tap-tap-tapping quickly into a room, start to turn,

and go into a skid every time, his little claws scrabbling on the slick

surface.

Although

we played endlessly after school, in school Joseph and I hardly spoke

to each other. He was in the fifth grade and I was in the fourth, and a

girl besides. When he was with other boys his age talking trash, he

seemed like a different person from the backyard drama director I knew.

My

friend Ginny said that when her kids were young, she noticed that they

did fantasy scenarios but their friends didn’t know how, possibly

because they weren’t read to. There is a difference between the

mostly-narrative picture book and the mostly-dialog television program.

Judy and I have been talking about this since we gave a storytelling

workshop together at the Music EdVentures conference. I noticed another

difference when I had two school residencies in Idaho, one after the

other, in upper-middle-class Ketcham and working-class Hailey. When I

asked fifth graders to make up a story as a class, the Ketchum kids

could do it handily, but the Hailey kids, with more TV and less reading,

started off just as inventively but killed off their characters before

much of a plot could develop.

Well,

even as I was typing that, the phone rang and I thought “That can’t be

Judy, she’s on her way to Japan,” and it wasn’t, it was somebody telling

me about a pre-approved home loan (watch out for those!) but I saw that

I had a message and that

was Judy, calling from a sports bar in the Seattle airport to say she

was noticing that dialog takes over not just in TV drama but in TV news

stories as well--in the form of interviews.

©2007 by Nancy Schimmel

Tuesday, April 10, 2007

RECESS