We

went to see the new river otter exhibit at the Monterey Aquarium last

week, and on the way we visited my second cousin once removed, Ed

Newman, and his wife Carol. I hadn’t seen them in at least thirty years.

“You look just the same,” Ed said, and I don’t, but I knew what he

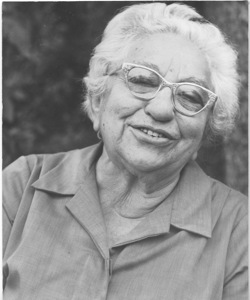

meant, because he looked essentially the same to me too. His mother,

Jennie, was my mother’s favorite aunt (she was just ten years older than

my mom) and my favorite of her generation. When I wanted to add my own

verses to Ruth Pelham’s Grandma song,

I realized I didn’t want to write about either of my grandmothers, but

about my great-aunt Jennie. I spent summers with her during World War II

when my mother was working in a bomb casing factory. Driving over the

Santa Cruz mountains took me right back to all the times I went there

with my parents. Here’s a piece I wrote from my memories of those summer

days for a class I took on writing children’s books:

THE BEST TREE IN THE WORLD

The best tree in the world grew in front of my great-aunt

Jennie’s house in Santa Cruz. It was a maple, and it grew at the front

edge of her lawn, so that half the tree overhung the street. Laurel

Street was a long, wide concrete slope that stopped a few houses above

Aunt Jennie’s. If I sat in the tree I could look several blocks down the

street without being seen myself. The limbs were set so that the tree

was easy to climb; the bark was smooth and comfortable. One stubby

branch was just the right size for child hands to grasp and swing on,

and the right distance above the ground to drop down from. It was

well-worn from the rubbing of my hands, my cousins’ hands, and the hands

of the kids three doors down. The maple was a place to play together or

alone. It was also a place to sit and think, away from grown-ups’

intrusions. It was the best feature of a generally interesting

household.

In the back yard were the chicken coop, a tangle of blackberry

bushes and the vegetable garden (I remember onions and artichokes). I

also remember debating with one of the neighbor girls whether an onion

pulled up from the ground was still alive. In the house were my capable

great-aunt and great-uncle and often a scattering of second-cousins of

various sizes and ages. Saturday nights there was a poker game to

observe, with chips to play with and cigar smoke to endure. Aunt Jennie

showed me the forming eggs in a chicken she’d killed and taught me to

make nine-patch squares. I further improved my mind by reading her books

(I remember only Mary Lasswell’s Suds in Your Eye) and by reading comic

books aloud to my younger cousin Freddy. Freddy had a b-b gun, and we

hunted snails with it in the blackberry jungle. When big cousin Eddie

was around, we would wheedle a trip to the beach in his jeep.

When I was the only cousin in residence and the neighbor kids

were away, I would go up to the end of the street and around the corner

to watch the waterfall where a little stream entered a culvert.

Dragonflies hovered over the water, and small trees and bushes shaded

the stream above the fall. Much later, when I read “water is heavy

silver over stone” it was this rushing, leaping water over stones set in

concrete that I thought of.

Then one summer we drove up to Aunt Jennie’s house and I didn’t

recognize it at all. The house looked suddenly smaller, exposed. The

whole street was bare. The maple was gone. I was shocked and

unbelieving. Aunt Jennie explained apologetically that a man had

persuaded her that the limbs over the street would fall off and crush

somebody’s car and she would be sued, so she let him cut it down. It is

the only time I can remember being disappointed in her.

Ed

told me that he didn’t get the jeep until after WWII, so I must have

ridden in it when I visited from Long Beach (when I was old enough to

take the train home alone) and conflated that memory with the earlier

ones.

The moral of this story is, don’t trust my memory!

I

called my friend Candy when I got home to recommend the river otters,

parents and five half-grown pups, rolling non-stop cuteness. Candy wrote

“Head First and Belly Down,” the river otter song on our CD Sun, Sun Shine.

And

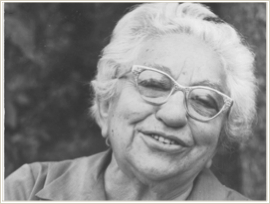

here is the portrait of Jennie as my professional photographer aunt

intended it, without the cropping necessary to fit in iWeb’s Procrustean bed.

PS

In the post for January 2, “Vocabulary” I quoted my father saying

“purest ray serene.” The other day I was looking for some poem (I can’t

now remember which one) in A Golden Treasury of English Verse.

I didn’t find it, but I started browsing around and, passing my eyes

over Grey’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” found, in the

fourteenth verse,

Full many a gem of purest ray serene

The dark unfathom’d caves of ocean bear...

I don’t know whether Grey made the phrase up or was using some commonplace of his time. Anybody?

©2007 by Nancy Schimmel

Monday, April 16, 2007

SPRING BREAK