Friday

I was in the office working on the lyrics website, looking at some lp

albums to double-check which Malvina songs had been recorded by whom. It

was a trip down memory lane. Here were all the original Limeliters

together, and there a youthful Pete Seeger. Some of the album covers

featured fresh-faced young women with “their hair...piled as sweetly as

the toppings on the pies” as Mom said of the waitresses in “The New Restaurant.”

One

of the songs on the list was “Work with Wallace,” from the 1948

election campaign, even before beehive hairdos. We don’t have a

recording of it, but, to my surprise, it is on two recordings that still

exist in some library. It was not one of my mother’s best efforts. We

don’t have a lead sheet, either, but I remember a snippet: “Since the

people’s party got under way,/Hope is the order of the day./You’ll find

yourself singing while the doorbells ring,/Work with Wallace and relax.”

I know what she meant—the worries of the world seem less menacing if

you’re doing something about them—but relax is not a word that sings.

For

those of you who came in late, this was Henry Wallace, not George.

Henry Wallace had been Franklin Roosevelt’s Secretary of Agriculture and

then Vice President (before Harry Truman), and ran against Truman and

Dewey on the Independent Progressive Party ticket. My dad spent many

hours standing on street corners in Long Beach garnering signatures to

put the party on the ballot in California.

On

the way home from the office, I was supposed to pick up two small

yellow onions, some lemon bubbly water, and bananas. I had my list, plus

seeing Mom’s song “Soul of an Onion”

reminded me. I was doing okay until a woman crossed the street in front

of me wearing a blue denim jumper, patterned cotton shirt, and straw

hat, looking attractively old-fashioned except she spoiled the whole

effect by talking on a cell phone. It got me thinking about the Renaissance Faire,

where I used to tell stories in the sixties. What do they do now? Do

they frisk people and make them check their cell phones at the gate?

Have little rustic booths that people can dodge into and use them out of

sight? So I missed the turn to the market and came home without and had

to go back.

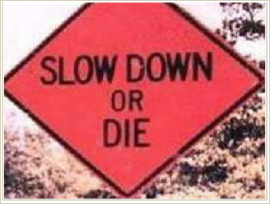

One

year I was driving down 101 from the Renaissance Faire in my little

flowered VW, and I got a ticket for driving too slow in the middle of

the three lanes going south when I should have been in the right-hand

lane. “I’m sorry,” I said, “I’m still in the sixteenth century.” I was

in costume, and the sympathetic police officer gave me the cheapest

ticket he could.

A few days ago I was going through some old emails (yet another

place for me to look for misplaced things, though better indexed than

the mess on top of my desk and the floor around it) and came across this

quote on appropriate velocity:

"Water

moving too quickly through a landscape does not

recharge underground aquifers. The results are floods in wet

weather and droughts in the summer. Money moving too quickly

through an economy does not recharge the local wellsprings of

prosperity, whatever else it does for that great scam called the

global economy. The result is an economy polarized between those

few who do well in a high velocity economy and those left behind.

Information moving too quickly to become knowledge and grow into

wisdom does not recharge moral aquifers on which families,

communities, and entire nations depend. The result is moral atrophy

and public confusion. The common thread between all three is

velocity. And they are tied together in a complex system of cause

and effect that we have mostly overlooked.

"There

is an appropriate velocity for water set by geology,

soils, vegetation, and ecological relationships in a given

landscape. There is an appropriate velocity for money that

corresponds to long-term needs of whole communities rooted in

particular places and the necessity of preserving ecological

capital. There is an appropriate

velocity

for information, set by the assimilative capacity of the mind and

by the collective learning rate of communities and

entire societies. Having exceeded the speed limits, we are

vulnerable to ecological degradation, economic arrangements that

are unjust and unsustainable, and, in the face of great and complex

problems, to befuddlement that comes with information overload."

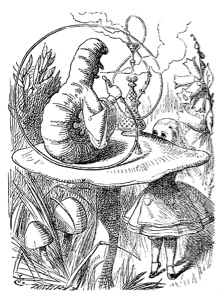

I

started going to my therapist again when I started writing the Malvina

bio, and last week we were talking about a moment in my life when things

happened too fast. She asked me to visualize what my younger self

needed to slow them down. I said “I’m seeing the caterpillar in Alice in Wonderland

sitting on his mushroom smoking his hookah—and what you smoke in a

hookah really does seem to slow time down—and he gave me a piece from

each side of the mushroom, one to make things go faster and one slower,

like he had given Alice pieces to make her bigger or smaller.”

I

reminded her that long ago, she had done a boundaries exercise with me.

She said she would walk toward me and I was to say when my

psychological boundary was crossed. She held a pillow in front of her as

she approached, and I was squished against the wall without saying

anything. Then she did the same thing more quickly, and I said “Stop!”

before she got near me. Now we have this cute new little adolescent dog

that most of the time I like except when I sit down on the couch and she

hurtles herself at my face. Then I have issues.

Some things just seem too fast—the rate at which babies get taller than their parents, for instance—but some things really are too fast.

©2007 by Nancy Schimmel

Thursday, July 26, 2007

VELOCITY