My

letter to the Times about their young hip librarian article got printed

in the Sunday paper, along with another letter about how as usual, the

article didn’t mention the important things librarians do—literacy

programs and all—but then, it was

the style section. It wasn’t that the students I went to library school

with in 1963-65 were intrinsically hipper than the library students of

the eighties, it was the times. I was commuting from Potrero Hill in San

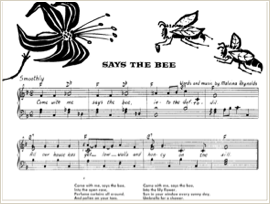

Francisco, first ride-sharing with Jodi Robbin, who was in grad school

in art, then with Margie Wilkinson, the daughter of one friend of my

mothers and daughter-in-law of another. Margie was working in the

administration building and drove a tiny Morris Minor. I drove alone

some days in my flowered VW bug and would usually pick up a barbecued

chicken from the co-op supermarket on University Avenue for dinner,

going into a kind of hunger delirium from the smell as I drove across

the Bay Bridge, getting the bird home intact by an exercise of

willpower. (Now that I think about it, I seem to remember that I did it

by putting the chicken in the back seat where it would be harder to

reach, though in a VW bug everything was pretty much in reach.)

When the Free Speech Movement

occupied Sproul Hall, I feared that my ride home, Margie, was in there.

I went in, and sure enough, there she was. I forget how I got home, but

the next day, when we found the police had dragged all the sitters-in

down the stone stairs, we went out on strike. Only two from the library

school were jailed, Virginia Walter, who became one of my best friends

later when we both worked at San Francisco Public Library and now

teaches in the library school at UCLA, and someone else, I forget who.

We were picketing the library building because it had classrooms in it,

and had to explain to everybody that we weren’t picketing the library

itself, it was fine with us if people went in there. Some of us went

around to explain to our professors what we were doing, and why. I had

never been a shining star in cataloging class, and our teacher, Mrs.

Frugé, always seemed distant—she lectured to the ceiling, not to us—so I

didn’t expect much from her. But when we told her about the police

brutality, she said “I understand perfectly. My family escaped from the

Nazis.” And when I thought about it, I

understood perfectly why the students were willing to risk jail or

expulsion to storm the administration building. Yes, it was about free

speech, but I remember so many times sitting on the steps of that

building at the beginning of a semester in tears of frustration because

some bureaucratic rule had kept me from doing something that seemed

perfectly reasonable and necessary to me.

For

instance, I needed only six units my last undergraduate semester to

complete my required units for graduation. For the first time, I didn’t

have a scholarship requiring me to sign up for at least twelve, so I

signed up for seven. The clerk said I couldn’t, it had to be at least

twelve. I went to the dean and asked why. He said, “If we let people

take take seven units, we’d have every housewife in Berkeley in here.”

Ten years later I would have thought him a male chauvinist pig. At the

time I just thought, “Not every housewife in Berkeley lacks six units to

graduate, you idiot!” Since I was working part-time, he let me take ten

units. What I did was sign up for a music appreciation class, which I

enjoyed. That final was my only test scheduled for the second week of

finals, so I skipped it and went off on my honeymoon. I flunked music

appreciation, the only flunk of my career, and one anybody would know I

did on purpose. So there.

My

favorite story about the Free Speech Movement was when the police went

into the president’s office and saw papers all over the floor and

assumed the students had trashed the place. “Oh, no,” said his

secretary, “it always looks like this!”

When

I was in my first job, at the Marina Branch in SF, I ran into Mrs.

Frugé at a California Library Association conference and told her I had

gotten a job at San Francisco Public. “Oh, you poor dear!” she said. I

was puzzled until I was transferred to the Sunset branch and saw in the

card catalog a subject heading Mrs. Frugé would never have approved:

Union of Soviet Socialist Russia.

My

father was a little disappointed when I went to library school. He

wanted me to be a labor lawyer or a diplomatic attaché or something. He

became reconciled to my choice of profession a few years later when I

came home from an American Library Association conference with the story

of Zoia Horn,

who went to jail for refusing to give the FBI the library records of

one of the Berrigan brothers. Those times have come again. Librarians

now have to deal with the “Patriot” Act, under which we not only are

supposed to turn over circulation records and internet use histories to

the feds, but not tell anybody we’ve been asked to do it. In Berkeley,

we erase records as fast as we can, and a lot of libraries do the same.

The American Library Association has put out a statement against National Security Letters, a form of administrative subpoena issued without judicial oversight or adequate judicial review. So there.

Sunday, July 15, 2007

THE SIXTIES: LIBRARY SCHOOL