We

were having a lively conversation about death this morning at

breakfast. It started out as a discussion of how and why religion

began—why people started believing in some kind of spirit world not

accessible to our waking senses. At first I was saying that people want

explanations, want to understand, and what we can’t find out we make up.

Then I thought about these last four months and said, “My partner’s

sister died in April and Claudia still can’t believe her sister is dead.

We saw the body, we have the ashes, but still she can’t believe. Who

can believe in death? That somebody so vibrant, so engaged today can be

gone tomorrow?” Holly said, “That’s exactly where I was going.”

Actually,

the conversation started with the Etruscans. Laurie had brought a book

about them to breakfast. Then we got into the beginnings of agriculture

and 1491 (which I reviewed on my books page)

and the development of maize. Scientists can’t explain how the early

peoples of the Americas developed corn from a wild plant that didn’t

offer enough sustenance for anybody to bother to gather. And corn as it

has been developed can’t propagate without human intervention. The

ancestors of rice and oats already had grains large enough and

accessible enough be worth gathering, and the refinement started from

there. Various Indian cultures have myths about corn being a gift from

the gods—could they be describing a sudden mutation that made corn worth

noticing? Is this what religions are made of? Wonder and gratitude?

That’s

when I jumped in with death, and the impossibility of believing that

our individual lives don’t go on. Laurie talked about her occasional

feeling that we are one with the trees and rocks and part of a larger

consciousness that she believes we go back into when we die, and that

our small consciousness is still somehow identifiable in. I do believe I

am a part of a totally interrelated biosphere, tree roots connecting

the trees to each other (Laurie threw in the inter-growing fungi here)

and my matter and energy will still be part of it when I die, but the

organization of that matter and energy into me

will be gone, and I don’t believe my consciousness will survive that

dissolution in any way. Then I said, “Ah, I think I know what I am. My

father was a Protestant atheist, my mother was a Jewish atheist, and I

am a pagan atheist. I don’t believe in the Goddess, or the Green Man,

but I do believe in rocks and trees.” And I do feel wonder and

gratitude. As Gren said over pre-breakfast coffee in relation to

something else entirely, “When you see fifty people doing the hustle you

know there’s got to be a god.”

My mother said it this way in an interview with Sheila Cogan in 1971:

When

I give a concert I talk a great deal. I not only sing my songs, but I

tell stories in back of them and I give my philosophy of life which

makes it possible for me also to appear as a minister in pulpits, a

godless child I--I have no religion at all except the religion of being

people. I’m not against religion. I think it’s a misnomer of being

human. Being human is such a groovy thing that people couldn’t believe

that it belonged to them--they thought God made them.

I

wrote a set of lyrics a while ago in response to the idea of “green

burial” in which we go back to the earth without polluting it with

embalming fluid and weed killer. It goes to the tune of an old song by Albert E. Brumley and uses the chorus intact.

I’LL FLY AWAY

One bright morning when this life is o’er,

I’ll fly away

Cycling through this world forevermore

I’ll fly away.

Chorus: I’ll fly away in the morning

I’ll fly away,

When I die halleluja by and by

I’ll fly away.

No embalming fluid will I have,

I’ll fly away

I will go organic to my grave,

I’ll fly away.

(Chorus)

When my delight in earthly pleasure fades

I’ll fly away

Get me a coffin that biodegrades,

I’ll fly away.

(Chorus)

When my molecules are all set free

I’ll fly away

As a bird or butterfly or bee

I’ll fly away.

(Chorus)

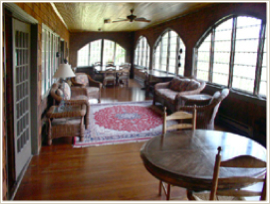

Now

I am in laptop heaven, sitting on a swing on a deck surrounded by oaks

and redwoods and firs and bay and I think a maple and none of the oaks

dead. Sudden oak death hasn’t hit Berkeley yet—the young volunteer oak

in our front yard is growing apace—but here nearer the ocean air it’s

hitting some species hard. I can see about five dead ones from Lydia

House, where I wrote this poem yesterday without realizing it was sudden

oak death I was writing about.

I glance out the staircase window

All is green except the center:

A brown tree picked out by the sun.

Brown leaves in August? too early.

Is it dead?

Dead and now in the spotlight

Like Emily Dickinson?

Like Van Gogh?

I

read somewhere that people in some culture in Africa believe that we

die twice: the death we all name as death and a second one when the last

person dies who knew us personally. Our poems, our paintings, our genes

may live on, but we die when we cease to move and breathe in the memory

of the people who survive us. So, if you want to live for a long time,

volunteer at your neighborhood elementary school or take your grandkids

out to see some trees and rocks.

©2007 by Nancy Schimmel

Tuesday, September 11, 2007

AT ST. DOROTHY’S REST